Money and Happiness: A Tumultuous Love Affair

Does money make us happy? Yes, except no, because, well, it's complicated...

“Money can’t buy happiness.”

“Money makes the world go round.”1

“It’s no shame to be poor, but it’s no great honor either.”2

“Greed is Good.”3

“More money, more problems.”4

Well which is it? Does money make people happy or not?

There are three answers. Two are obvious and intuitive, but wrong. The third is more nuanced and probably right.

Money and happiness are locked in a tumultuous love affair, forever connected, but always fighting.

Money is Bad

It’s easy to find people who say that money is evil.

Perhaps the best-known condemnation of money comes from the eccentric Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope:

The love of money is the center of all evil.5

One reason this claim is so well known is that it’s repeated in the Bible:

The root of all evil is the love of money.6

So, according to these sources, wanting money is bad. This sentiment is often abbreviated to “money [itself] is the root of all evil,” even though that’s not what the ancient authors say.

It is however what Sophocles says:

Nothing has ever sprouted that is so evil for people as money.7

The foundational Plato agrees:

It is impossible for people to be both very rich and good.8

And, over 2,000 years later, so does the transcendentalist writer and philosopher Thoreau:

Absolutely speaking, the more money the less virtue.9

For these great thinkers, money itself is bad. And they’re not alone. In agreement with them are St. Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscan Order (12th century); Catholic theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas (13th century); philosopher and social critic Jean-Jacques Rousseau (18th century); Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy (19th century); American novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald (20th century); reggae musician Bob Marley (20th century); and many more.

Money is Good

Equally, we don’t have to look far to find people who praise wealth, and they often have the numbers to back up their claims.

In the US, Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton found10 that money makes people happier. In a separate study, Matthew Killingsworth found11 the same. (The first study claims that money only makes people happy up to a threshold of about US$90,000, while the second study argues that money makes people happy beyond that. Matthew Killingsworth, Daniel Kahneman, and Barbara Mellers reconcile the results,12 suggesting that unhappiness continues to decrease with more money, even though happiness doesn’t rise as quickly.)

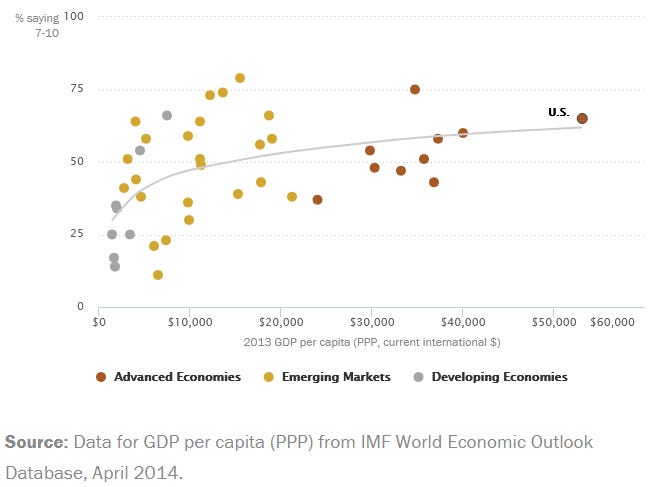

The Pew Research Center found similar data across the world.13 People are generally happier in countries with more money per person, and “richer people are more likely than poorer people to report being happy with their current life situation,” no matter what country they live in.

Were all of the philosophers wrong? Is being rich simply good? No, because:

Money is Bad, Revisited

It’s not just philosophers who think money is bad. Lots of real-life experience points in that direction.

For instance, Eric Weiner reports14 a chilling experience he had in India, where, to his horror, he ended up renting an apartment with a servant. But the servant was only 11 years old — “a cultural difference that [Weiner] was not prepared to accept.” In the end Weiner tried to help boy, and it didn’t go entirely well. He had “raised his expectations,” he writes, “a dangerous thing in a country of more than a billion restive souls.”

And I have personally seen more happiness among the poor in India than among the wealthy in the US. (Read more: “The Smiling Vendress in Old Delhi.”)

So there seems to be ample evidence that money makes people happy, and also ample evidence that it doesn’t. What’s going on?

Who is Rich?

Seneca gives us an important clue in a quotation from Antipater:

Poverty does not mean the possession of little, but the non-possession of much; so it is not defined by what it has, but by what it lacks.15˒16

He also says, in his own name:

It’s not having little, but desiring more that makes a person poor.17

This gets to the core question left unanswered by the the Pew Research Foundation and by Killingsworth et al.: What counts as rich?

These ancient authors suggest that the answer is relative. People who have little are not necessarily poor; and people who have a lot are not necessarily rich. Rather, people who want more are poor and people who want less are rich.

People who have little are not necessarily poor; and people who have a lot are not necessarily rich.

We shouldn’t be surprised.

For instance, most people throughout history have (obviously) had no electricity or running water. Does that mean that they were as unhappy as you or I would be without those “basic necessities”? No.

Similarly, it’s better to be rich than poor. But there’s no direct connection between having things and being rich.

I’m again reminded of India, of a girl I saw carrying water when I thought she should be in school. Was she happy or not?

Lessons

So what do we learn?

We learn that it’s complicated. Money and happiness are locked in a tumultuous love affair, forever connected, but always fighting.

As a practical matter, the best we can do is know that we have to walk carefully. It’s a mistake to think that money doesn’t matter for happiness; it does. But it’s also a mistake to think that money makes us happy; it doesn’t.

So go ahead. Work hard. Earn lots. Buy nice things. And give to charity.

And at the same time, if it’s happiness that you’re after, don’t stop there.

Cabaret, 1966.

Fiddler on the Roof, 1964.

Wall Street’s Gordon Gekko, 1987.

The Notorious B.I.G., Mo Money Mo Problems, 1997.

Τὴν φιλαργυρίαν εἶπε μητρόπολιν πάντων τῶν κακῶν. Diogenes of Sinope, c. 350 BCE, as quoted in Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Diogenes, VI.50, 3rd c. CE.

Ῥίζα γὰρ πάντων τῶν κακῶν ἐστιν ἡ φιλαργυρία. I Timothy, VI.10, 1st c. CE.

Οὐδὲν γὰρ ἀνθρώποισιν οἷον ἄργυρος κακὸν νόμισμ᾽ ἔβλαστε. Antigone 278, 5th c. BCE.

Πλουσίους δ᾽ αὖ σφόδρα καὶ ἀγαθοὺς ἀδύνατον. Laws 5.742e, 4th c. BCE

Civil Disobedience, 1849.

“My Servant” in The New York Times.]

Paupertas enim est non quae pauca possidet, sed quae multa non possidet; ita non ab eo dicitur, quod habet, sed ab eo, quod ei deest. Antipater, Fragments No. 54, c. 100 BCE, quoted in Seneca, Ad Lucilium, LXXXVII.39, 1st c. CE.

Here Seneca, probably rhetorically, editorializes: “I myself cannot see what else poverty is than the possession of little.” (Ego non video, quid aliud sit paupertas quam parvi possessio.) Elsewhere (below, e.g.) he agrees with Antipater.

Non qui parum habet, sed qui plus cupit, pauper est. Ad Lucilium, II.6. 1st c. CE.