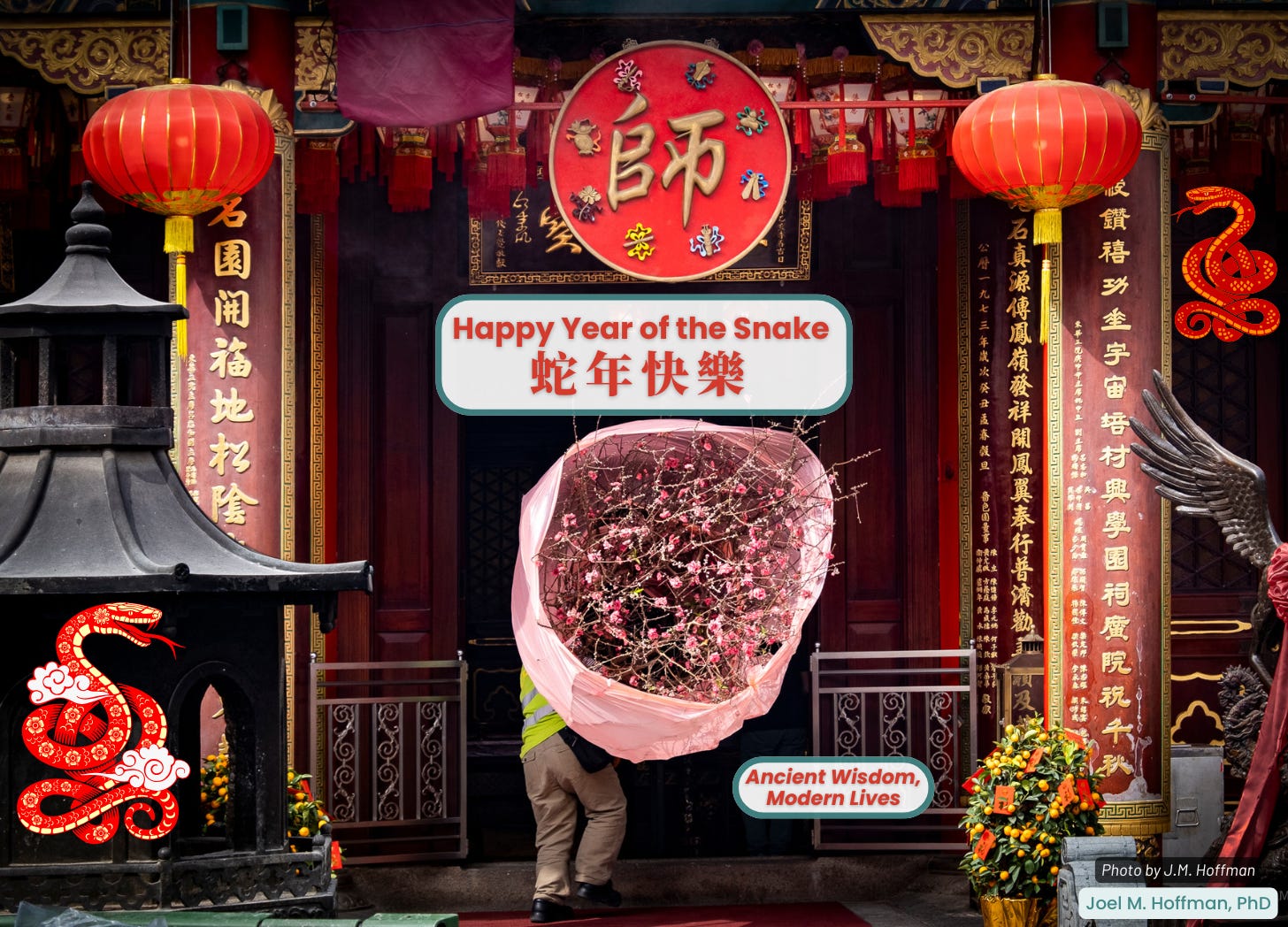

Happy Year of the Snake

Why is there a year for such a despicable animal as the snake? There might be a very good reason...

Snakes have a bad rap.

The most famous portrayal of a snake is from the Bible, where it is the source of all human misery. The snake in Genesis coaxes the first humans to disobey God, and this leads to their downfall. We have been suffering ever since. Another source, also from about 2,000 years ago, clarifies that the snake is the very embodiment of evil.

To this day, calling someone a snake is a particularly heinous insult.

And beyond the metaphor, real snakes elicit particularly acute fear and loathing in most people.

Why then would we want a whole year in honor of the snake? There might be a good reason.

The Snake

In addition to its role in the Bible, the snake has been associated with evil since at least the days of Greece.

Aesop writes of a man who sees a snake in winter. The snake is almost dead from cold, but the man rescues it, warming it against his body. Once the snake revives, it bites and kills the man. The man’s dying words are that he deserved to die, because he took pity on the wicked. The snake represents wickedness.

The same basic image appears in Phaedrus’ Fables1 (and Erasmus’ Adagia)2 and, much later, in Chaucer and Shakespeare.

Similar in point are reversals such as what Demodocus of Leros describes, where a snake bites a Cappadocian, but it was the snake who died because the Cappadocian’s blood was so vile.3 Voltaire uses the same insult.4

While Matthew (10:16) uses the snake as a symbol of wisdom — “be as shrewd as the snakes and as innocent as the doves” — this is most likely a direct reference to a wordplay in Genesis. There the snake is called “the most shrewd,” but the Hebrew for “shrewd” sounds like the Hebrew for “naked,” and the point is that the snake, along with Adam and Eve at this point, are all innocent.

But the snake also features prominently on the Rod of Asclepius, the ubiquitous symbol of medicine.

Snakes are connected not just to evil but also to healing.

Why?

Many people think it’s because snakes shed their skin, a process reminiscent of healing.

The Year of the Snake

As my friend Ka Yan points out, this may be the blessing of the year of the snake. We, too, have an opportunity to shed our metaphoric skin and to define ourselves anew. We don’t abandon our essential core, of course, any more than snakes do.

But we get to leave some things behind in the year now ended. We can ask ourselves what no longer works for us, what we have outgrown, or, perhaps, what never fit us in the first place.

Then with a fresh slate of opportunity, we can decide who we want to be in the world. And, with a whole year of possibility in front of us, we can take our time and grow into our new skin.

Happy Year of the Snake.

蛇年快樂! 🐍

“Columbram sustilit sinuque fovet, contra se ipse misericors.” Fables, IV, 18, 1st c. BCE.

“Serpentum in sinu fovere.” Adagia, iv, ii, 40, c. 1500 CE.

Καππαδόκην ποτ᾿ ἔχιδνα κακὴ δάκεν· ἀλλὰ καὶ αὐτὴ κάτθανε, γευσαμένη αἵματος ἰοβόλου. Epigram (in Greek Anthology, XI, 237), c. 450 BCE.

“Hier auprès de Charenton, // Un serpent mordit Jean Fréron. // Que croyez-vous qu’il arriva? // Ce fut le serpent qui creva.” Imitation of Demodocus, 18th c. CE.